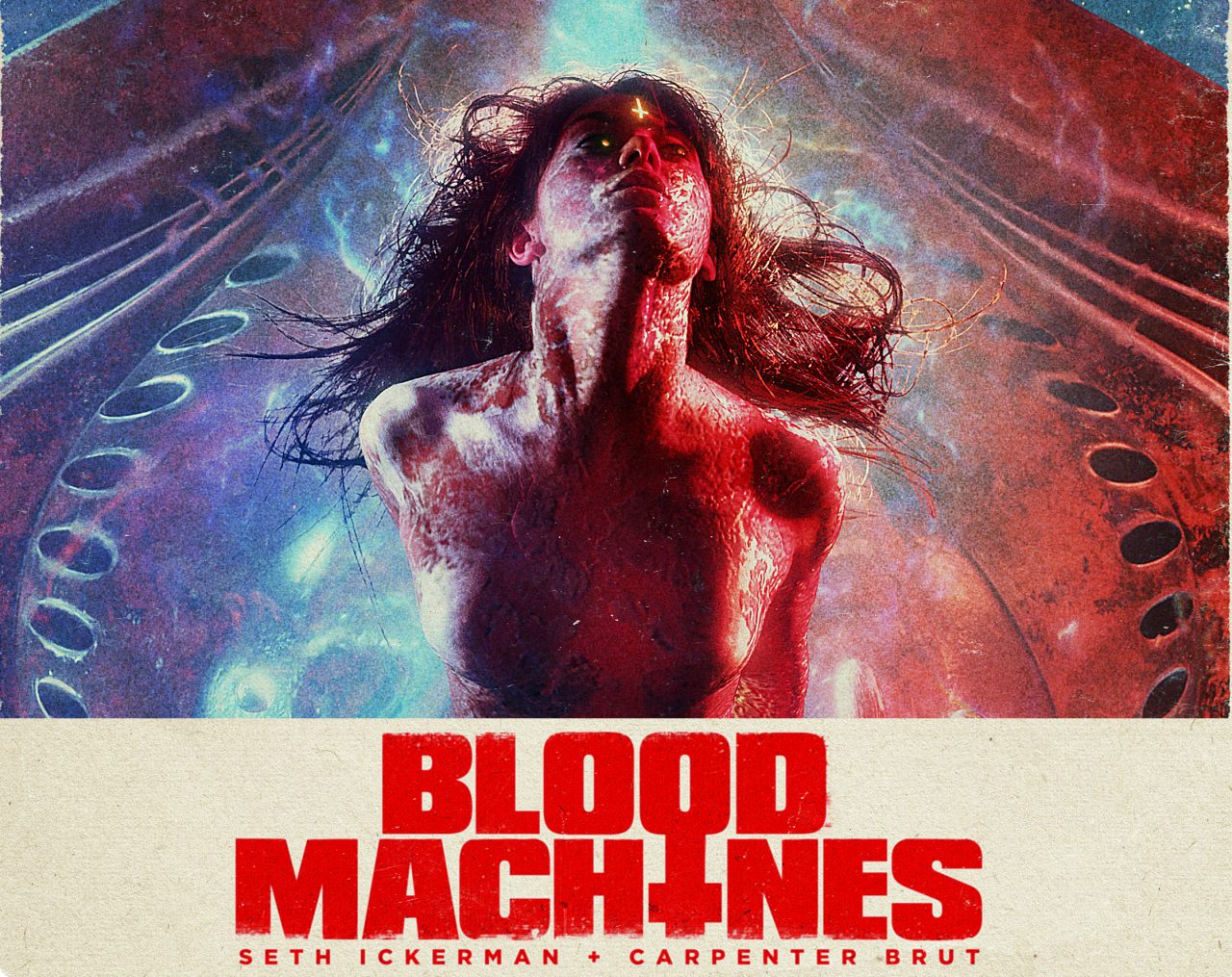

After three years of tireless efforts to deliver what is hyped up to be the Retrowave movie experience of a lifetime, Seth Ickerman has recently announced the near completion of their widely anticipated Blood Machines Space-Opera feature. Pitched as a follow up to the jaw-dropping thrill ride that was Turbo Killer, the upcoming French sci-fi epic will notably feature an original score by Carpenter Brut, which will potentially go down as the darkest, loudest and heaviest Space Opera soundtrack ever conceived. Following a hugely successful Kickstarter campaign launched in late 2016, the Ickerman duo has recently decided to launch one final crowdfunding campaign to fund the film’s finishing touches. Having met the duo three years ago to talk about the project (link), I got in touch with the restless pair to garner the latest news since our initial meet-up. I caught up with Raphaël and Savitri last Saturday afternoon at their studios. Raphaël had told me that weekends were a long-lost memory by this point, as the two had started working seven days a week, including days that went from 9 am to midnight. Having run out of funds, the duo has taken it upon themselves to deliver on their promises by locking themselves into what could reasonably be compared to China’s infamous ‘996 Working Hour System’. After a quick tour of the studios, we sat down in the office’s dining room over coffee to discuss the latest developments on Blood Machines.

Last time we met, you had just launched the first Kickstarter campaign back in 2016. How’ve things been going since then?

Raphaël : We’ve been holding up, but it’s been complicated at each step of the way. We estimated our first Kickstarter campaign goal according to our reach and it was a great success. The film isn’t only being financed by Kickstarter. We’re currently working on a budget that’s around half a million euros. We’ve had to find other sources of financing through our producer at Logical Pictures. It was tricky for them, too, considering that this music-heavy project doesn’t quite fit any standard format and that we didn’t want to compromise on that end. To top it all off, it’s also a costly project to pitch. Before shooting, we had to make sure everything fits within reasonable boundaries to get things started.

We had the resources for about fifteen days of shooting, which was pretty tight for us. We went through a few 1st AC’s (First Assistant Director), because a lot of them didn’t think it was possible. We had to find someone crazy enough to understand what we were after and bear with us. The shooting went well, actually. We found the right people who were on the same page, but it was pretty tough. We had a very tough schedule and we had to constantly come up with solutions and workarounds to fit everything in. We had to cut a few things we managed to shoot what we needed to shoot.

Savitri : We prepared a lot beforehand since it’s a special effects film and we had to know precisely which shots we were going to shoot. Changing an angle or technique adds up a ton of effects in post-production. You can’t really improvise on the set.

R : We used film sets, we filmed outdoors, we shot at night… we went through all of the tricky situations but we got through it with some luck. We dodged a storm!

S : We shot outdoors for three days and it was bad weather on the third day, but it’s true that it could’ve been worse.

R : Coppola used to say that no matter if it rains or snows, you should still shoot. You’ll justify it later. [Laughs]

Last time you explained that this project was characterised by hybridisation of your « garage-film » work such as Kaydara and a more professional workflow. How did you perceive this newfound work organisation?

S : It was indeed a fifty-fifty mix between both worlds. We had a full team on set and everything, it was great. We were able to focus on work as directors and we didn’t have to handle everything as we did on Kaydara. The « garage » aspect came from the fact that we built the sets three months beforehand ourselves. We handle the special effects too, although we do have people helping. We still handle a lot of aspects. There’s an artisanal side t

o our work that makes sure that our film will end up being made, only we sometimes need to do things ourselves. The shooting was great, but there was inertia that we weren’t always able to control. We used to work at our own pace on our garage projects, so we’re not as comfortable working this way. There’s a whole team behind us that cannot work more than nine hours per day.

R : We had a lot of different crew members come into work for a few days before passing things over to the next team. We weren’t able to keep the same crew for the whole duration with the budget we had, let alone pay for overtime. We had to respect their personal lives.

S : We had to make the most out of what we had, which made things intense. Being a director basically consists in explaining what you’re after. The same goes for special effects. Our inertia is different. It takes more time to get what we’re after. It’s great to have people lend a hand but it’s also complicated, you struggle to get what you’re after. When we were in our garage and no one cared, we were free to do whatever we wanted. We had the space to go through with everything, there were no limits.

R : Working on such an ambitious p

roject forces us to compromise on quite a few things we would have never done in our garage. With that being said, making a film that didn’t look like one of ours was completely out of the question. It’s a struggle to keep the balance. We’re very attached to our artistic integrity and we’re not making this film for money so that that’s all we have. This film isn’t going to make us rich [Laughs].

S : Our job as directors is to focus on explaining our vision so as to translate our world into images. This is a hugely ambitious project that would have taken us an extra two or three years to finish, had we done it in our garage.

R : Roughly the same time it took for Kaydara, basically [Laughs].

Would you call this ‘Do-it-yourself’ approach a passion or rather a necessity? Would you still keep this same approach for a multi-million dollar film project?

R : Not like this. We’ve suffered too much on this project, quite frankly. It’s about finding the right balance, which we didn’t have on this one. I don’t know what we were smoking when we wrote the story! [Laughs]

S : It’s mostly due to the fact that we come from the « garage » world, where everything is possible. There’s no money but all you need is time. Everything is possible to us, really, but when it comes to creating an economically viable product that needs to fit within a certain budget, it’s a whole other story. Our production company still backed us, nonetheless. When you see how much such a project costs, it simply doesn’t make sense to make a film like this, considering that it’s not going to make any money.

R : It’s our gift to humanity! [Laughs] I’d hate to sign for a 200 million dollar movie where I don’t have my creative liberty. Actually, maybe not, I’d probably think about it if I were offered the opportunity … [Laughs]. Nevertheless, the genre films from the Seventies and Eighties that I loved had an artistic identity to them. It’s all about balance. Making a film with such a tight budget compared to its level of ambition is extremely hard to pull off. You basically destroy your social life. You can easily do some things better with a bit more money. There’s no use in having a disproportionate amount of funs, only enough to get things done properly. We’re a lot more lucid now when it comes to what we need to make our films.

S : There are no miracles. A bigger budget means less freedom, as producers want to take fewer risks. Even big directors have to face this. We’ve got some freedom, but a tighter budget also comes with a certain number of other constraints. Making a movie necessarily means making compromises. It’s impossible to make the exact movie you had in mind, and you have to accept it.

R : Bear in mind that we’re making a fifty-minute movie with roughly half a million euros, which is nothing compared to what we’re doing from a technical standpoint. Our first estimates from special effects companies had us looking at half a million euros for half the film, with all technical specs stripped to a bare minimum. We’d have needed twice the budget and we wouldn’t have had the results we were after either. I don’t even think it would have even worked out.

S : People who’re great at what they do don’t work for cheap.

The movie has gone from a thirty-minute format to fifty minutes. Which aspects did you choose to develop with this extra runtime?

R : The movie hasn’t necessarily been developed, plot-wise. It’s just that the movie is very visual and the cinematography is very stylised, so everything took an entirely different aspect than initially planned when it came to actually piece things together.

S : We storyboarded the whole film with a thirty-minute 3D animatic, but it was impossible to tell exactly how long everything was going to last. Once you’re on set, everything finds its own dynamic and its own pace.

R: Our style is a little more old-fashioned, with a more contemplative pace, so things lasted quite a lot longer. Each small addition ended up accumulating, which led us to this fifty-minute edit. We didn’t shoot anything more, it just naturally evolved that way.

How’s the collaboration going with Carpenter Brut? Is the Soundtrack finished yet?

R: Almost! It was a new experience for both of us. He had already done stuff for other directors but never a proper score. He’s said himself that he’s more of a song composer. It was a special learning experience and we had to find our marks as well. I think he found himself a little bit constrained on certain aspects. It wasn’t easy, but I think we’ve reached a cool balance. I don’t think he would’ve written this score on his own, it’s something different. We pushed each other outside of our comfort zones, and the result is a fairly hybrid piece that you don’t really come across in movies nowadays anymore.

So the film was scored with the images in mind?

R: Yes, which made things pretty tricky. You can’t really understand much from simply watching the first edit.

S: The actors are interacting without anything around or in front of green screens. It can be tough to understand what’s going on. It’s easy for us because we know animatic by heart. It was also tough to write the music while the film is being made, as changes required adjustments on both ends.

R: He would sometimes send us a first demo and we’d explain what the scene would look like to help him make edits and adjust the tracks. It shaped up bit by bit in that way.

Did you adapt the edit to the rhythm of the music?

R: It’s really a language. It’s really complicated to make any changes because of the special effects. You need to be precise, which is a constraint. On his end, changing something in the music can also come with a certain number of constraints. That’s the tricky part when it comes to creating both the film and the score simultaneously. Sometimes he’s changed things, sometimes we’ve adapted.

How did this DIY approach of yours come about? Was there any particular work that inspired you?

R: We never really purposely drew inspiration from anyone when it comes to our way of making films. We simply wanted to tell stories and do what we wanted, so we learned everything and progressed for that purpose. Savitri made a lot of models, which came in handy for our Sci-Fi films. He then developed his skills in 3D animation because we needed it. We make things because that’s what we want to do, really. If we were given the means to not have to handle certain aspects of production, we’d simply keep an eye as art directors. We want to keep and respect our artistic vision. There are too many constraints in doing everything ourselves. It’s a waste of time.

S: We just don’t have a choice. We want to make films with the means that we have.

R: It’s fun to make models and the artisanal side is always interesting, nonetheless. Films suffer when there aren’t enough practical effects and too much green screen. We chose to shoot with an old Panavision lens with heavy optical aberrations because that’s the image we like in Eighties films. It’s awesome but it causes a lot of problems. The image isn’t all smooth but that’s what gives it character, though does make things complicated in terms of special effects.

S: The artisanal aspect is awesome. It’s great to be able to do everything from start to finish, but I’d gladly take the opportunity to simply focus on the artistic side of things while others work on rendering the visual effects and building sets and props. We’ve done enough. It would also harness better results. We handle everything because we don’t have a choice, and this approach has its limits. It’s great, but I can’t wait to simply work on the artistic side. We gained another level in order to go further, as we have with each film. What we want is to focus on our vision, not necessarily craft it with our own hands.

R: Having done all of this will also help us in leading our teams.

S: … and understand the process better. Bad special effects aren’t necessarily the fault of the designer. It’s also part of the director’s vision. If a visual effect doesn’t work, it’s also his fault.

R: There are films with huge budgets with botched special effects. Money isn’t the issue. The issue is with artistic vision and choices.

S: Having the means to your ambitions is also a talent, it’s part of the game, too.

Was it hard to share your workload with a team?

S: It was complicated.

R: We don’t trust people! [Laughs].

S: People can’t read your mind, so they sometimes do the opposite of what you want [Laughs]. Redirecting people requires time and the skills to lead people in the right direction. Other times you just don’t have the resources to keep someone long enough to finish the work they started.

R: That’s what our weekends are for. We enhance and adjust certain things.

S: There’s also a certain balance between what we do and the teamwork. Everything blends together into something coherent nonetheless.

R: Savitri goes over everything during the colour grading process, for instance.

S: We’re working day and night for free because we want to and because it’s our film.

R: We also have obligations towards our backers. We need to deliver something and we can’t simply spend six years in our garage.

S: We also want something substantial, too. We don’t want to lower our standards. We’re working hard on maintaining them, even though it’s completely absurd to spend so much time on a film that’s not going to earn us anything. It’s already great that we’re able to do this, though. It’s impossible to make films like these in France. We didn’t get a single French grant as of yet.

When do you think the film will be finished?

R: We’re sure that we’ll finish it this year. Our Kickstarter campaign will help pay for a few more VFX artists to help us optimize certain things.

S: The film will be done this autumn but we don’t know yet when exactly it will be released.

Any closing words?

S: Thank you to everyone who supported us on this adventure and to all of those that have yet to support us! [Laugh]

Interview conducted and translated by Robin Ono

A huge thank you goes out to Alexis and Seth Ickerman for making this interview possible.

Don’t miss out on this opportunity and join the adventure. Visit Blood Machines’ Kickstarter page to learn more!

Seth Ickerman