In the 21st Century, when we think of “early video game consoles,” we think quaintly back our box-like gray NES or perhaps our handsome wood-paneled 2600, and we feel a sense of belonging – a sense of rooted nostalgia – in the sense that our childhoods were part of video game history. It’s only right that we do; these and other innovative machines broke new ground for their time and raised the bar for future development. We think of those names… Nintendo, Atari, Sega. Ancient and noble they sound.

The beginning of things was far more humble, but it was a beginning, and a beginning is all it takes.

Born in 1922 in the southwest German town of Rodalben, Ralph H. Baer emigrated with his family to the United States just two months prior to Kristallnacht in 1938. A family of Jewish origin, the Baers feared persecution in Germany and sought a new life in New York. Starting his American dream in a factory at age 12, Ralph eventually graduated from the National Radio Institute in 1940. He went on to be drafted in 1943, assigned to military intelligence in England. GI Bill money enabled him to pursue his Bachelors degree upon returning home to America, which he received in 1949 from the American Television Institute of Technology in Chicago. By 1956, Baer was working at a New Hampshire defense contractor called Sanders Associates, where he oversaw a crew of some 500 engineers who developed electronics systems for military use.

As a side project, Baer began working on the idea of an electronic home game system in 1966. For three years, he and two associates Bill Harrison and Bill Rusch, developed a series of seven prototypes for the device. It was this seventh design, dubbed “The Brown Box,” that the trio successfully pitched to Magnavox in 1971. The California-based consumer electronics company (whose name means “great voice” in Latin) saw merit in the idea of a home arcade that a family could hook up to their own television set. Hands were shaken, paperwork was drafted, and the Age of the Console had begun to rise and shine its first rays over a quiet horizon.

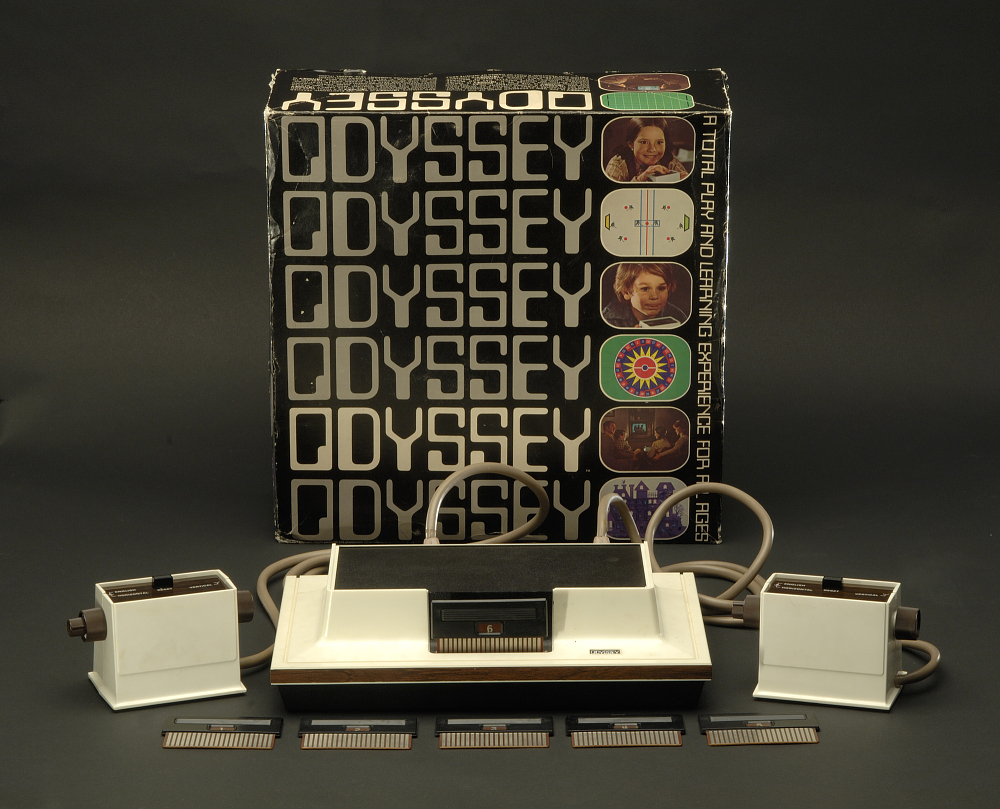

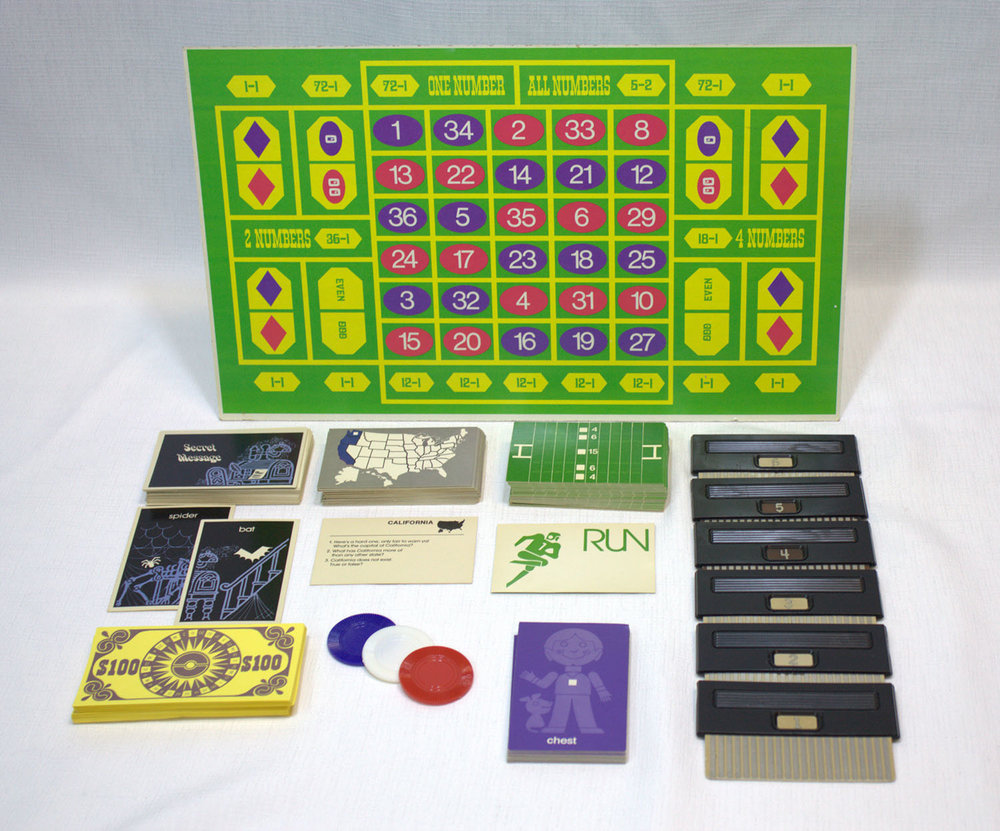

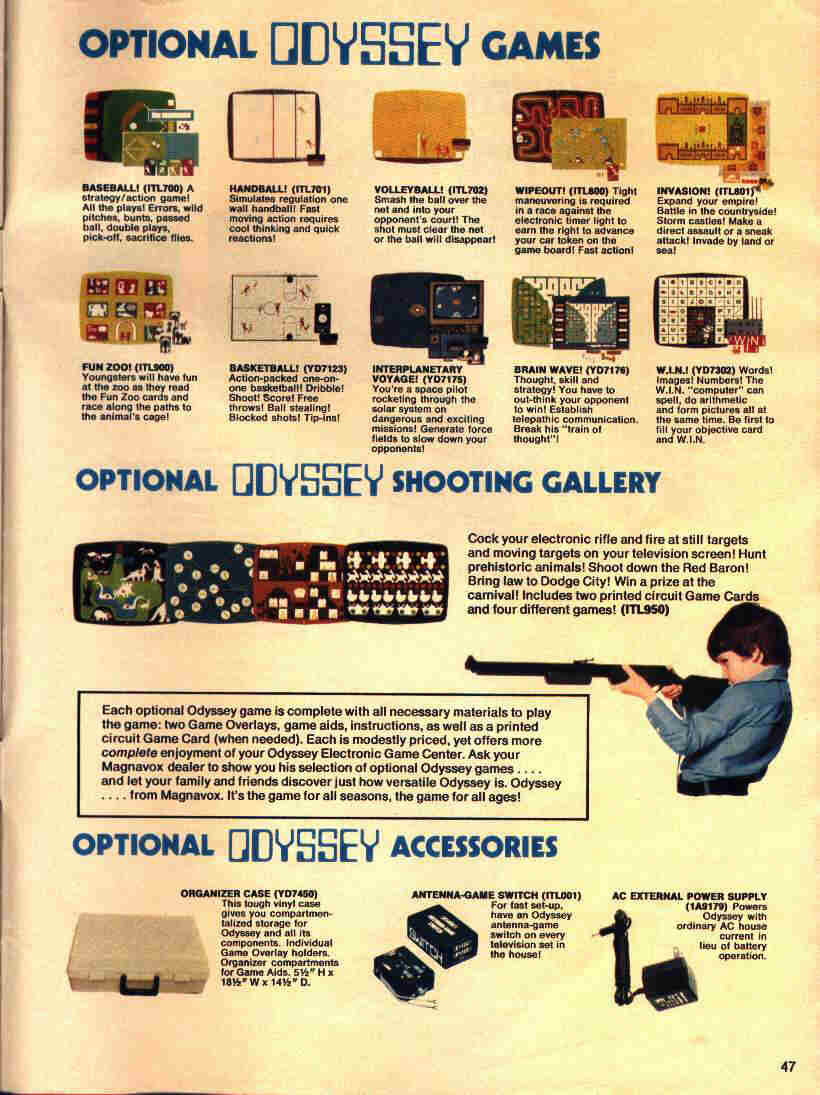

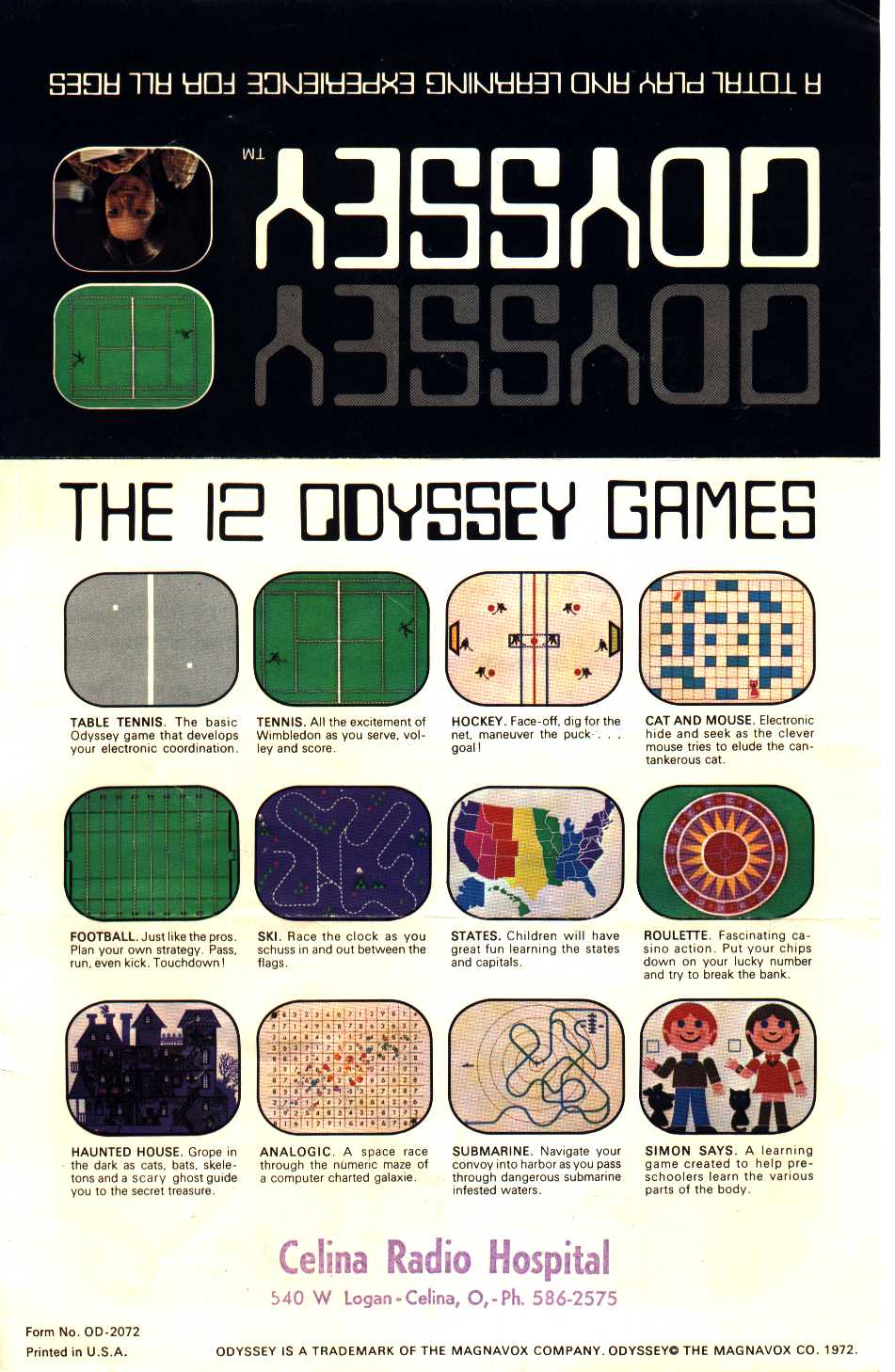

Clockwise from upper left: The original Odyssey suite and packaging; the physical paraphernalia for various games; two pieces of promo/ad copy, one of which details the core game library, the other advertising the Shooting Gallery accessory (the first light gun for a home console).

A simple, unassuming white-and-black plastic box also featuring that ever-stylish 1970s wood-paneling texture in a few places, the original commercially-available Odyssey was a wondrous machine to the consumers of 1972’s America. While to modern eyes it may look more like something you’d see controlling a kitchen appliance or a sewing machine, this was a fully-functional electronic device! The Odyssey could be powered by an AC adapter or six C-cell batteries, at the owner’s option. It connected to one’s television by way of a switchbox, presenting itself to the TV as a channel. The arcane device bore with it two similarly-garbed controllers, each of these being slightly bigger than a Band-Aid box and bearing one button and three knobs. The button was used to reset certain display elements during play, while the knobs were used to control the movement of said elements.

These “elements,” before screen-mounted visual overlays and the users’ imaginations were applied, consisted of one large square of white and two smaller squares of white on a black background. That was literally the cast & props of every Odyssey game. These games were simply sets of parameters and behaviors, fed into the system’s motherboard by one or more printed circuit boards; All 28 games playable on the console were generated from a final set (as of 1973) consisting of 12 cards. The most complex game was Invasion, which require cards 4, 5, and 6 to play. The games came with the aforementioned color overlays, to be placed over the screen of the TV as both a visual aid and a sort of “game board.” You see, the system itself didn’t even adjudicate the games’ outcomes or scores; players had to to that themselves, too. As a matter of fact, the console and some games came packaged with “accessories,” such as playing cards and paper money, to further facilitate the actual playing of a structured game. In essence, this ancestor of the modern home video game console was little more than a tool… or perhaps more aptly, one of a set of tools, used to play games. Perhaps most age-indicative of the Odyssey’s traits was the now-obvious total lack of audio capability. There was no sound output whatsoever, presenting a 21st-century observer with a heavy and eerie silence as the Odyssey does its work.

Magnavox began retail sale of the Odyssey system in September of 1972, setting the MSRP at US $99.99 (or just $50.00 when bought with a Magnavox television set). During its inception, Ralph Baer had estimated an optimistic $20 price point for the console, but the addition of extra elements and the usual corporate desire for profit drove the price higher, something Baer is known to have seen as upsetting. While reports from various sources conflict with one another on the exact number of units produced that first year, it is known that somewhere between 120,000 and 140,000 were made. Similar conflicts exist regarding the units sold that year, with the sum ranging from 69,000 to 100,000. While the sales were low overall due to a fairly high price for the Odyssey (in 2017 dollars, the cost translates to almost $600) and a misleading notion that the system only worked with Magnavox TVs, there was enough continuing demand for production to continue through 1973’s holiday season as well. This coincided with a late 1973 ad campaign, resulting in an estimated sale of 125-150,000 units through ’74.

Lawsuits were rampant during this period, as copycats and lookalikes were spawned by various other electronics companies trying to duplicate or cash in on the phenomenon’s buzz. Most Notably, a 1974 suit by Magnavox against Atari, Bally Midway, and other major amusement companies over both the game design and the programming methods used to create them, constituted the emerging VG industry’s first major lawsuit due to copyright infringement. Similar court cases erupted in rapid staccato throughout the 1980s and 1990s, including defendants like Nintendo, Coleco, and Mattel. These court cases not only established the backbone of civil law regarding video games as a commodity, but also made Magnavox and Baer a lot of money (in the hundreds of millions).

Ralph Baer was awarded the National Medal of Technology in 2006, and his groundbreaking console is represented in both the Metropolitan Museum of Art (where the Odyssey is part of a permanent installation) and the Smithsonian (where Baer’s prototypes are kept in the American History part of the institute). In 2014, Baer died at age 92, having given birth to a new age of electronics and home entertainment through his innovative work in the development and commercialization of home video games.

When it was eventually discontinued in 1975, conservative estimates place worldwide sales of the Magnavox Odyssey at about 350,000 units. While significant, this net result was not considered a smashing financial success. The “Odyssey” brand would continue through the 1970s with successive dedicated consoles (playing only built-in games) and eventually the iconic Odyssey2 in 1978. It is from this point onward that the “early history” of the video game console ends and the commercial video game industry truly begins.

Once again, thank you for reading… and NRW Gaming wishes you a Happy 2018, and so do I. I look forward to continuing our walk together through the future, as we keep the past alive. Stay Retro!