Two is the beginning of the /beginning/.

James Matthew Barrie /slightly purified/

Yes, the publication date in parentheses is correct. I have dared to leave the safe zone of our beloved 80’s for the conceptual sake of presenting you two texts about two books which are radiant manifestations of yet another double concept – the immobilization inside and outside of time. At first glance, it may look as if our good old Amonne is about to spill yet another bucket of pretentious balderdash onto our shoes or, more likely, eyes, thus divesting us of our already rare everyday “commodity” – time. I am going to contradict this assertion by showing that due to magnificently random occurrences, one is bound to experience new combinations, fuses and concoctions of sensations (the term “sensations” has been used here for lack of a better word; perhaps a portmanteau of the following: “swarming”, “exhilarating”, “contrivance” and “internal” would serve a better purpose, however I do not have time – how ironic! – to come up with portmanteaus left and right). Sensations of time reversals which would make Benjamin Button green with envy, eternities frozen in timelessness so immovable and stationary, that thermal fluctuations at temperatures nearing absolute zero would look like some mosh pit madness at a death metal concert. But enough with these exaggerated disposable comparisons.

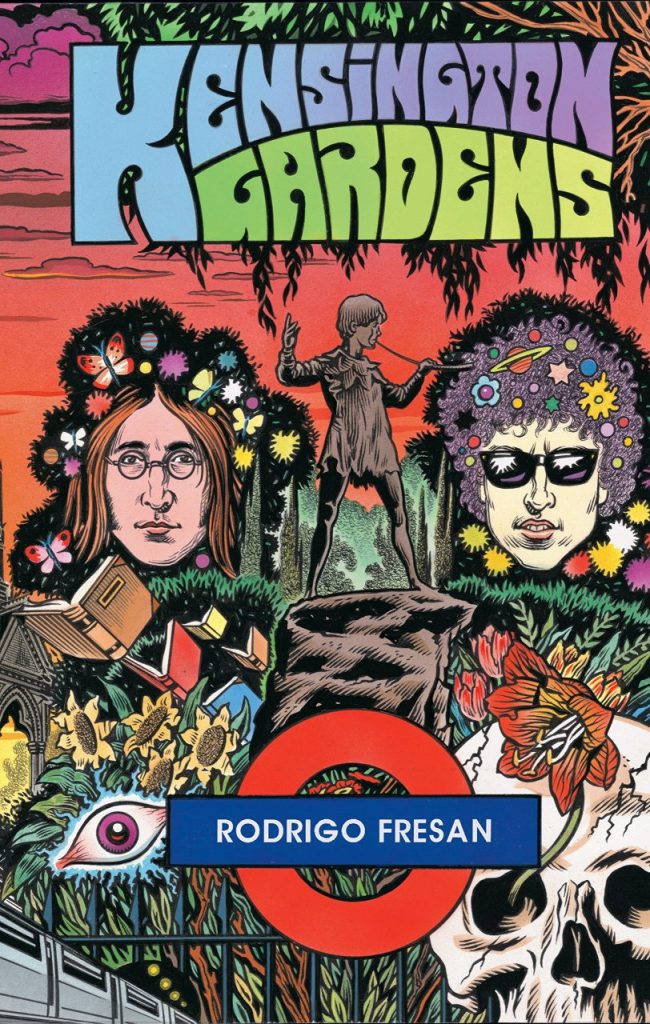

Kensington Gardens is this particular type of book which not only falls under the “exclamation marks” category without much effort (the abundance of quotable profundity found in it is absolutely staggering and would easily serve as a so-called “brilliance content” for at least three or four other novels – we draw exclamation marks next to the dazzling passages almost on every page!), but also courts us with its multilayeredness in a flawlessly natural fashion. Rodrigo Fresán’s work takes us on a truly wondrous trip to the late Victorian/Edwardian London as well as to its LSD-driven Swinging Sixties incarnation whose freshly regained poshness of a global city, which has just got up off its knees from the post-World War II era of food rationing and blandness, helped to set standards for how the modern world would look for the remainder of the 20th century. Poking the issue with a stick would quickly reveal that it involves a consolidation of questions regarding “mechanics” of a certain kind of day-to-day aesthetics: in what ways things would be perceptible, how would they expose themselves in front of us, what would their meaning sound like for us, etc. But all of these are just some generalized yet very marginal notions, almost unworthy to mention, which might pop up inside our heads as we glide along the pages. Besides, we do not want to put the cart before the horse, do we?

One of the main threads of the book is the life of a Scottish writer James Matthew Barrie – the creator of Peter Pan character which was first introduced in a 1902 novel entitled The Little White Bird and immortalized in a play Peter Pan; or, the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up two years later. Barrie’s life is recounted in a highly detailed and simultaneously unusual way biographies-wise, for it mysteriously intertwines with recollections of a man who narrates it. The reminiscences of this man, whose name or occupation I shall not reveal (taking into account the new “feelings” Kensington Gardens generates, that would be quite a spoiler), evoke his childhood memories as the Swinging Sixties kid who, almost as if under influence of some sort of magical powder (no innuendos!), had the occasion to experience firsthand the crème de la crème of the delirious 60’s ambience. His parents played in a rock band and therefore all sorts of big names orbited around in his immediate vicinity (David Hemmings, Dennis Hopper, Stanley Kubrick, Catherine Deneuve, Jimi Hendrix, Jean Shrimpton, Dean Martin, Peter O’ Toole, Audrey Hepburn, Andy Warhol, Vidal Sassoon, Jimmy Page [solo, no Led Zeppelin then], Peter Sellers, Phil Spector [way before his gun and hairstyle frenzy], Philip Larkin, Brian Jones [without The Rolling Stones], The Rolling Stones [without Brian Jones], Michael Caine, Kray twins, Timothy Leary, to name but a few). These remembrances, which far too many times have been peppered with a sour and tragic seasoning of unfortunate events, constitute the second thread of the novel and – married in an effervescent mixture of awe and stellar warmheartedness with Barrie’s unorthodox biography – play first fiddle in Rodrigo Fresán’s “thread trio”. What plays the second one?

Second fiddle and, by the way, the third thread of Kensington Gardens – a bit undercurrent-ish and, frankly, quite pivotal one – turns out to be purely psychological. Now, as you may or may not know, I loathe psychological novels with every fiber of my being. They are one of the most, if not the ultimately dreadful, hopeless, dragging-down boredom generators ever contrived by humanity. Do you want to experience the utter disappointment of internal ruminations which lead from never to nowhere? Just take a good look at yourself in the mirror after you have rinsed your mouth during the morning session of teeth brushing. Why read about somebody else’s monsters when you can look at yours any time you like? To empathize? To feel catharsis? I have never understood that, just as I have never been able to comprehend, how on earth talking to an allegedly smart bearded stranger with grizzly hair, who wears a black jacket over dark burgundy turtleneck and a pair of brown corduroy trousers (I am being awfully stereotypical, but I guess I could be excused – my licentia poetica is my Savior and only She can judge me…) would help cast the demons out. But I am getting self-sidetracked… There are, of course, exceptions, e.g. Dangerous Liaisons by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos or The Diary of a Seducer by Kierkegaard (the latter could be found in the first volume of his Either/Or) whose psychological facet is always cut unintentionally, plays the part of a byproduct which is never assessed as the main reason for a novel to appear, or is smuggled subtly from an area where the fuzziness found between the lines meets the murkiness of silence (like brackets within parentheses). The same goes with Fresán’s wonder – the psychological wanderings of his protagonist are somewhat of a result of the idea which exists behind the novel, perfectly ingenuous, deprived of this unmistakable, toxic, regular psychological ingredient which pulverizes your soul mercilessly and turns you into a drowsy creature which yaws wider than hippo’s obtuse snout could possibly open. If you want to throw in some stuff form the brown leather couch, you had better make it innocuously inconspicuous – like Fresán has done. And this, My Fellow Readers, is the highest possible form of compliment from someone who fights like cat and dog with…ahem…psycho novels.

Putting threads of Kensington Gardens back into the haberdashery of belletristic knickknacks, let’s talk about magic. For Fresán’s novel surely deserves this noun to be placed in its description. What is so mesmerizing in this delightful book? Apart from Barrie’s life – his daydreamlike and tragic childhood, first steps into the not so adult, yet dull and adulterous world of adolescence, youth and journalism, meeting and turning the Llewellyn Davies brothers into his own, later on – private, pantheon of Muses, unimaginable and splendorous success of the Peter Pan play, divorce with his wife Mary, the revenge of Demons that lived within him, within the only author who remained ageless enough to write about and personify the immobilization and rejection of the growing up, and who suffered fully from the dire consequences of the above deed – apart from the sweet-and-sour critique of Swinging Sixties and the psychological scarring of the protagonist, Kensington Gardens introduces us to something really luscious. The tasty raisins of ruminations (e.g., a marvelous comparison of literature’s development to certain stages of human life – from its innocent birth in 18th century, via Wonderlandly-Twisted 19th century childhood and turbulent Caulfieldishly Hazy excesses of its 20th century pubescence, to… oh, you almost got me! Naughty, naughty!…), mouth-watering custard pie of predictions about humanity, literature, perception of history, and the like, along with some other delectable morsels – for instance the genesis of a name Wendy – all of it creates this highly flammable orgy of unforgettable literary flavors and elicits imaginary opiate and/or LSD trips to somewhere where there is no ticktock of a clock playing an infinite game of Tic-tac-toe with us. Where noughts and crosses do not spawn endless combinations of nevermores. Where everybody does not have to be a lucky loser or just a plain one – beside, outside or – the worst of them all – inside oneself. Where there are no bad monsters living under our beds or hiding behind closed doors of our closets…

Now, what’s with this “immobilization inside time” Kensington Gardens is responsible for bringing along? Does it have anything to do with keeping everything “frozen” in the eternal stupor of metaphysical obligation of something to be? Or maybe of something to pass? When does it start? Why does it have to be so surreptitious? Here we go, hitting a brick wall again… Nonetheless, if I gathered up my courage to set my doubts aside for a while, I would say that Fresán’s novel does not eject us outside of time. Our presence is well within its boundaries, its plane of influence, its realm of conditionality. However, we are not moving anywhere along it. The most accurate and, at the same time, describable phenomenon which could illustrate the above is this extremely rare and comparatively short-lived subjective time dilatation. It happens when you enjoy something so utterly that you are not only totally disconnected from the rest of the world (no, its not the regular immersion à la GTA: nothing-else-matters-when-I-play-it-San Andreas) but, given the circumstances, you do not even conjecture in a mode of: “Holly crap, I feel as if someone’s just activated bullet time!”. It resembles sitting on a moving bus or a train with all of its windows shut tight. You remain perfectly motionless and the interior of the bus/train is something which redefines the term “astonishing”. Personally, I think it can only occur before you are ten years old. After that – sorry buddy, maybe next time (you’d better pray for the reincarnation in human form to be true!). I myself have experienced it only once: when I watched a movie called The Brave Little Toaster. I must have been no more than 8. And I swear to God/Contingency/Flying Spaghetti Monster/Whatever Demiurge at hand, the movie lasted six hours! Now go check out on IMDb how long the movie really (really?!) is if you care to do so. Kensington Gardens gives you the similar “feeling”. The “feeling” of elfin supremacy Stanley Ipkiss possessed while wearing the titular mask. The “feeling” that taking part in somebody else’s dream inside a dream inside a dream, etc. seems like a child’s play. The “feeling” that you have just been metaphysically rewired and you immediately forget about it, like Peter Pan. It is like a crescendo of a big band consisting solely of children’s first laughs seconds before breaking into thousand pieces to form fairies: unbearable in the beginning, nevertheless, after a while, purely (dis)obligatory, indestructibly innocent, irrevocably courageous. The laugh that blurs the line between the promise, sacrifice and fulfillment. The laugh that solidify our innate internal armor which cannot be pierced through. Not even by pointy, razor-sharp teeth of the ticking crocodile which ate our hand once, and has wanted more ever since. Perhaps, he prowls because he is still missing some hands for the clock inside his stomach? Who knows…

This is how extraordinarily unique Kensington Gardens are. But there exists its perfectly pitched counterbalance, orchestrated by the second part of the concept I have focused on in the previous paragraph – the immobilization outside of time. The only thing I am going to disclose now is the fact that in order to present the said opposite I am going to leave the 80’s one more time and head towards some other decade. What decade? What kind of novel is my next trip going to be about? As for now, my lips are sealed, however you had better keep your eyes open, because I do not intend to put a lid on my inkwell just yet.

Amonne Purity